Will America Make Robots?

Robots that have long lifespans, interchangeable components, and accessible maintenance will be the path to securing America’s robotic future.

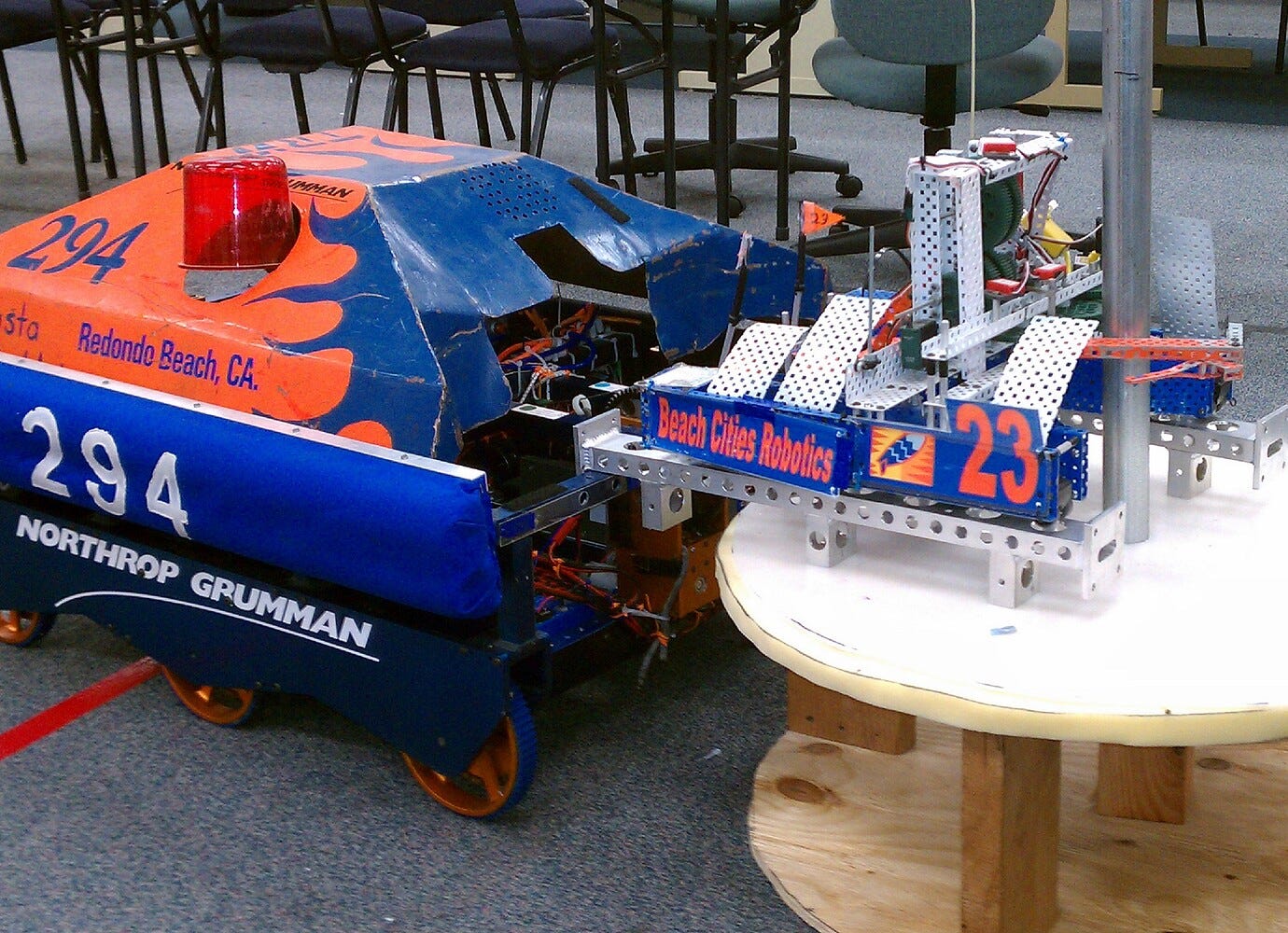

My first projects involved machining and lathing parts for competitive robotics; a hobby largely inspired by the DARPA challenge. Then I spent the last decade building apps for laptops and smartphones. The trillion dollar question for Americans making parts will be whether robots look more like DARPA’s self-driving cars or more like smartphones.

Will our world be full of cheap disposable machines being built offshore, or will there be a robust manufacturing and servicing industry born from more intricate and durable machines?

We see impressive demos every week, but they raise fundamental questions about manufacturing scale that I don't think the industry has adequately addressed. The gap between a working prototype and a mass-produced product is years of R&D of its own, particularly for physical goods with hundreds of components sourced from global supply chains. What do we need to get right for these awesome demos into production, and what do end customers really want their robots to look like?

Making there robots in America will require significant capital investment, skilled workforce development, and long-term commitment to compete against established supply chains. The national security implications of robotics dependency may justify this investment alone, particularly for aerospace and defense applications where cost is not the primary constraint. I care more about the grand prize of mass production. America’s role in manufacturing entirely depends on the lifecycle and the price point the end market wants.

Price point & supply

If the price point and lifecycle of robots looks like consumer toys or sub $2000 units that are incredibly task specific, it’s inevitable that we end up designing incredibly integrated machines that will be disposed of within five years. If really useful robots cost $50,000+, these are high cap-ex investments that will need to be financed. This usually also means a market to maintain and extend the lifecycle of these machines to draw out as much value as possible. These are black and white examples. In the former case, the US plays a minimal role, and in the later the US plays a strong one.

The market has not converged on a price point for general case robotics, and all signs indicate we’re going to end up in a messy middle between electronics and cars.

Let's take humanoids as a case example. On the lower end, Ben Bolte wants to deliver a $8,000 product that's composable and can be remixed to perform specific tasks effectively today. Elon Musk aims to create a more premium product that costs around $30,000 but is better equipped to handle greater variance in requests autonomously. The nuance lies in the underlying design of these systems. The market as easily converge toward either high-end consumer electronics or an intricate OEM process resembling automobile manufacturing.

This discussion remains largely hypothetical since no vendor has achieved real scale yet. Current robotics companies focus primarily on software and system integration, but mass production demands expertise in component sourcing, supply chain management, and manufacturing processes that most of these companies lack. No standard playbook has emerged across robotics companies due to significant variation in design approaches and product philosophies. When robotics experiences its "ChatGPT moment," many of these details will become much clearer.

For today, we can focus on breaking out four major areas that will be essential for robotics manufacturing, each accruing value in different ways.

1: Big three components

The three major component drivers in robot manufacturing are PCBs, brushless motors, and injection molded materials. Robots need numerous printed circuit boards for processing, sensors, and microcontrollers. Brushless motors enable movement, with humanoid designs requiring more motors to create additional degrees of freedom. Structural components and casings primarily consist of injection molded plastics. China has developed significant advantages in PCB and motor production, which raises serious questions about supply chain resilience and America's competitive positioning in this market.

Brushless motors represent a materials and manpower challenge. The magnets require rare earth elements, and the precision manufacturing requires skilled workforce development. Apple's investment in Chinese manufacturing capabilities (rumored to be $55 billion / year) has created a skilled labor force that has proliferated throughout Chinese industry. This creates a significant cost disadvantage for alternative manufacturing locations.

PCBs represent China's most developed manufacturing ecosystem. The Chinese have solved instant quoting, developed sophisticated design-for-manufacturing processes, and automated most of their production pipeline. The ecosystem is sufficiently developed that replicating it elsewhere would require rebuilding much of the integrated circuits supply chain.

Injection molding presents a stronger opportunity for American manufacturing. The die creation process still relies heavily on skilled craftsmen with tribal knowledge about temperature, pressure, and material flow relationships. This creates both a bottleneck and an opportunity for process optimization and automation. Companies that can systematize this knowledge could achieve significant competitive advantages.

2: Mechanical Design → Production

Robotics companies are poorly prepared for the complexities of hardware procurement. Unlike software companies that can scale with a few clicks on the AWS console, robotics companies require hundreds of specialized components produced on an ongoing basis with different suppliers, lead times, and failure modes. Even large scale consumer hardware (laptops and phones) don’t have nearly the same amount of manufacturing complexity. There’s probably linear curve in complexity with the degrees of freedom hardware might have with the complexity of scaling it’s production.

Consider the BCN3D-Moveo robot arm as a simple example with 5 degrees of freedom. This open-source design requires structural components, fasteners, bearings, motors, and power systems. The motors alone require rare earth magnets, high-conductivity copper, and precision manufacturing capabilities. Each component category has different optimization criteria: cost, weight, reliability, and manufacturing complexity. Each complication in the supply chain of any component makes the end product exponentially more complex. Robots in our world will be far more complex than the Moveo.

Robotics company founders are thoughtful about product and designed problems. Only the best know much about getting parts, working with suppliers, or making products at scale. This creates a strategic vulnerability where a single hiccup in the supply chain can halt production entirely. Given the amount of components, robotics supply chains might end up being really long and complex! Most startups have tried to solve this problem by directly stealing talent from automotive or aerospace because this is the talent that’s readily available in America. Neither market shares enough of the same workflow or design challenges to directly translate into robotics.

3: Assembly

Robotics companies are assembling robots in-house. Mostly because no one has moved more than 2,000 units. This could continue like the automotive model (Tesla, Ford) or shift to the consumer electronics model (outsourced to contract manufacturers). The choice depends on the feedback loop requirements between design and production.

In-house assembly provides several advantages during the early development phase: rapid iteration, resource optimization, and quality control. When product designs are still evolving, having the production line adjacent to the engineering team enables tight feedback loops that are difficult to replicate with outsourced assembly.

The question is whether this arrangement persists as the market matures. In the automotive industry, most successful companies have maintained in-house assembly for their core products. In consumer electronics, most companies have outsourced assembly to specialized contract manufacturers. Both cases are a direct result of where value accrued for each business. For American manufacturing to be involved, the robotics industry will likely need to follow the automotive model due to the complexity of calibration, software optimization, and quality assurance processes. The less complex the underlying supply chain, the fewer opportunities to create new optimizations that differentiate from the ones in consumer electronics.

4: Service & Support

Robots, like cars, have physical components that degrade over time, require maintenance, and need periodic upgrades. This creates service location-dependent and relationship-intensive service opportunities: a recipe for decentralization.

In commercial applications, there will likely be significant demand for forward-deployed technical talent. As manufacturing, retail, food service, and construction become increasingly automated, job functions will shift toward maintaining automated systems rather than performing the work directly. This could follow the Microsoft partner model: specialized companies that understand both the technology and industry-specific requirements.

The consumer market presents additional opportunities. Like cars, most consumers will not develop sufficient technical expertise to maintain complex robots independently. If the market moves toward $8,000+ humanoid robots rather than isolated single-purpose machines, there's a business case for specialized support networks providing delivery, setup, training, and maintenance services.

Some value accrues at the service layer if multiple robot manufacturers compete in the market, similar to how the physical complexity of cars led to a network of dealers and repair shops.

What about America?

The robotics market will be moving toward mass production. The question now is if they'll be made in America, or our country will focus on service and integration opportunities.

Service and integration present clearer opportunities. Companies that develop expertise in robot deployment, maintenance, and upgrade services can build defensible businesses with recurring revenue and high switching costs. These businesses require local presence and customer relationships rather than manufacturing scale.

The question is whether focusing on services provides sufficient competitive positioning as the market matures. In the automotive industry, manufacturing capability has remained a core competency for successful companies. In consumer electronics, product companies have captured most of the significant value while outsourcing manufacturing.

I believe the robotics industry will follow something closer to the automotive model due to product complexity and the crucial feedback loop between design and production. This stems from the consolidation we've seen in consumer vehicles and what I expect consumer robotics to resemble. However, robots could potentially follow the consumer electronics path instead. If that happens, China's advantages in the consumer market would likely be insurmountable, as those advantages directly translate from electronics manufacturing.

Maybe none of this matters. Like all great technologies, the largest chunk of value will accrue to end users of robots, and not necessarily to those who manufacture them.

But as an American I do care that we have a reliable supply for the greatest wealth enablement in human history. Investing in robots that have long lifespans, interchangeable components, and accessible maintenance will be the path to securing America’s robotics manufacturing future.

The big unlock for U.S. robotics isn’t AI, it’s domestic manufacturing of motors, PCBs, and molded parts. If we treat robots like appliances, we’ll offshore them. If we treat them like vehicles, we might actually build them here. This is the kind of thing I'm tracking in my own writing.